If here’s one thing that can stir the blood as much as a presidential campaign, it’s a nice raft of juicy ballot propositions. Our are a bit thin on the ground this year, but include at least one really nice zinger to catch national news attention.

To be honest, I do these blog posts for two reasons. One is to advocate. But the other, frankly, is to contemplate. Like the article last night said, actually having to explain why a policy position works tends to slow one down, moderate views, and really make you think about what you’re saying. Or it does for me, at least.

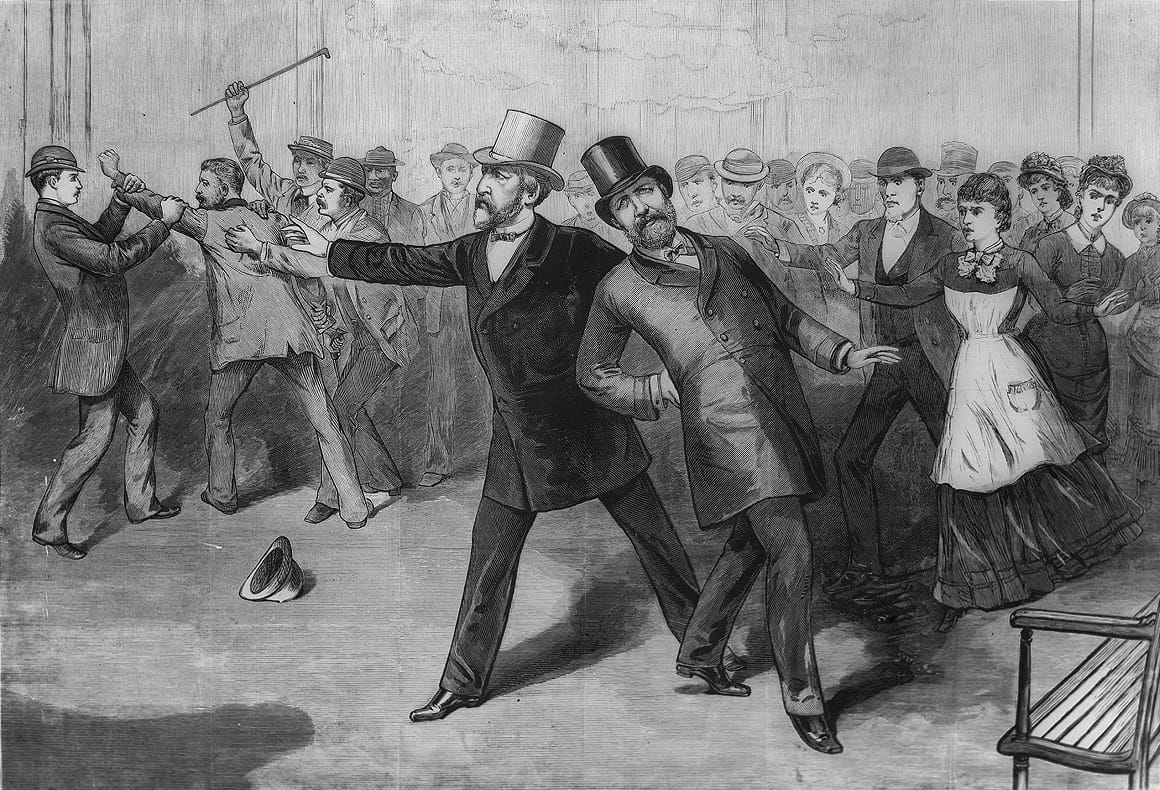

Amendment S affects the Civil Service provisions of the Colorado Constitution. The Civil Service was put into most governments at the dawn of the 20th Century as a reaction to the Patronage system. Patronage basically said, “Hey, My Guy just got elected, so let’s see if he’ll give me a job.”

If you win today as, say, governor of Colorado, your department heads and chief advisors and “inner circle” are basically yours to play with, but get down a couple of levels and people are protected by the Civil Service (or the State Personnel System here in Colorado). They can’t just be fired at will and replaced with political cronies and people you want to reward for their campaign support. Under the Patronage system, certainly at a national level, much of a President’s first year was taken up with an endless stream of job applicants for any federal job under the sun, and it used to be the same story at the state level.

The Patronage system was also known as the Spoils system — as in, “To the victor belongs the spoils.” The reward of winning office was not just the power of the office itself, but the power of awarding other office-seekers (and their friends and families) jobs.

Colorado’s Civil Service dates back to 1918, with a big update in 1970 (at which time it was renamed the “State Personnel System”). It covers around 32,500 jobs in mostly the executive branch and offices around the state. There are currently about 41,000 “non-classified” state employees, folks uncovered, by definition, from civil service — mostly judicial, legislative, and state college employees. Mostly higher-up positions in the state government –policy-makers, “managers” — are non-classified. The Civil Service rules require that employees by hired and promoted by merit and fitness, applicants be scored by competitive exam with hiring decisions made from the high scorers, that positions be filled by Colorado residents, and that applicants have a year’s probation before they become part of the system.

Prior to the Civil Service (and, no, this isn’t a binary all-or-nothing decision, but …), all non-elected positions in the state government were effecitively at will, which meant that a new Governor could name his friendly next door neighbor (or the guy who contributed $250 to the campaign) to some nice state government job. And, usually, did. Because once everyone’s a political appointee, then it only makes sense get rid of your predecessor’s appointees (esp. if they were from the other party) and replace them with your own. That doesn’t do much for government efficiency of course, but it does encourage political favors and campaign contributions.

Amendment S works to weaken these provisions in a variety of ways, some more or less defensible. That always makes me a bit leery, to be honest, since I always approach that kind of thing with a cui bono (who profits) attitude. The power to grant “spoils” is a corrupting power, antithetical to the purpose of the state to serve the people. That was the purpose of the Civil Service system, and anything that weakens it had best provide distinct advantages.

Here are the changes in Amendment S:

More political appointees: Amendment S lets the state personnel director designate an additional 1% of classified jobs from the Civil Service, making them at-will political appointee positions. Most departments currently have just one exempt position — the manager a the top. Now you can have more — the assistant director, finance and HR managers, etc. It’s not a huge number, but it strikes me as a camel’s nose under the tent flap. It makes more managers/administrator’s into potential political patronage targets for the Governor.

But because it’s such a small number, and presented as the most prominent part of the proposal, then it will probably promote shrugs. It’s not a huge number, but … who benefits by it?

Less stringent testing standards: To fill a Civil Service position, you have to test and rank all the applicants, and then choose from the top three scorers. The amendment lets you come up with other “professional” and “objective” ways of ranking applicants — search committees, etc. — and then lets the hiring manager choose six candidates for the final decision, even if they are not the top scorers per the testing (which thus become a guideline, not a requirement).

The public rules for this will be set by the Governor-appointed state personnel director, rather than the State Personnel Board (see below).

The argument here seem to come down to flexibility (should Department X be able to figure out the most desirable way to pick candidates) vs. objectivity (should Department X be allowed to select candidates with pretty much no restrictions). The Civil Service rule should, in theory, set objective criteria across the state for a given type of position. In practices, that’s not necessarily ideal for a given hiring manager, office, location (and doing well on a test may not be the best way to figure out who is the best hire). On the other hand, depending on how the Governor’s state personnel director sets the rules, this would let the rules be change to allow more patronage to take place.

A bit more preference to veterans: Currently, a veteran (or surviving spouse) gets a “bonus” to add to their test score (5 point in the 100 point exam; 10 points for a disabled vet), but only gets to do this for the first successful hire, after which they can’t apply it to a new position applied for. The Amendment lets vets carry that bonus on to other applications all their lives.

This provision is probably a good one. While one can argue whether it creates a little inefficiency (in theory it could help a less qualified vet beat out a more qualified non-vet), it seems a reasonable trade-off to reward for such service.

It’s definitely the sweet spot of the legislation, in fact. I mean — who could possibly turn down something that helps veterans?

Which makes me suspicious, in fact, because it is a very clear sweet spot. And to my mind, if I look more closely here, it’s actually a lot less meaningful of a reward than it seems. Because per the previous changes, the test scores aren’t nearly as critical any more. Hiring managers can also pick candidates from a wider pool of “highest-ranked” people, regardless of that test score bonus.

It’s bait and switch — here’s something that looks more valuable (under the current system) but is actually less valuable (under the proposed system).

More temporary employees: Currently, temps can only be brought into a Civil Service to fill short-term / urgent hiring needs for a maximum of 6 months in a 12-month period. The amendment extends that to 9 months per 12-month period.

The arguments for say this will allow for better being able to meet “seasonal demands” — but, crikey, if you’re talking 3/4 of the year, that hardly seems “seasonal” to me. It might end up letting some one-off projects operate more efficiently with contractors, but is also means is that state offices can fill permanent positions with temps if they can get by with a 75% FTE for the position, saving money and turning more regular jobs with benefits into temp positions. I don’t think that’s a good thing.

More out-of-state employees: The current system says that all state Civil Service jobs be filled by state residents (unless it requires special qualifications and a Colorado resident can be found with them).

Amendment S provides a little flexibility to eliminate the residency requirements if the position is located within 30 miles of the state border. Since most of our state borders are fairly sparsely populated, that’s not a bad idea.

On the other hand, the Governor-appointed state personnel director also gets to waive residency requirements for any position in the system. Arguments for say this allows for more flexibility again for special jobs. But there is already a provision for making exceptions; this just makes it easier to appoint an out-of-state supporter to a government position without their having to establish residency. Maybe that sometimes gets you a better person. Maybe that sometimes means rewarding a political contribtor.

Reduced Civil Service oversight: Policy for the Civil Service system is handled by the independent State Personnel Board, none of whom are in Civil Service, which includes 3 appointees by the governor and 2 elected by the classified employees. They are currently elected or chosen for 5-year terms, and cannot be removed from office by the Governor. The amendment reduces terms from 5 to 3 years, term limits them to 2 terms, lets the Governor remove two appointees at “pleasure”, shifts rule setting for the hiring process (including residency requirements) to the Governor’s state personnel director.

This is both the policy-wonkiest and most insidious of the provisions. It seems to significantly weaken the independence of the Civil Service system both by removing big chunks of power to a direct Governor’s appointee, and by making its management much more beholden to the Governor’s whims. It’s less important what the rules are, if the folks administering and setting the rules are more subject to direct influence.

Summary: Pro-S folks basically seem to say, “Run state offices like private businesses. Just as a private business can hire anyone they want, from wherever they want, and fire them if they want, state positions should adopt that same flexible, efficient, responsive model.”

The problem is, state government isn’t the same as private business. Private business runs on profit, which means efficiency, which means conservation of employees. If a new boss takes over as president of the company, it’s not in her interest to replace all the employees with her friends (most of which didn’t play any role in her taking over the business), just, perhaps, and business-cautiously, some of the top jobs. There’s no benefit to her to replace other groups that are doing well.

State offices don’t run on profit, they run on providing services and represent an exercise of state power. In the case of the state, the top boss may change every four years, and may have very different ideas as to what services should be provided and how to exercise that governmental power (and on whose behalf). The Governor may be much less interested in whether the citizens served by a given group are getting what they need, as much as the benefit of appointing a friend or contributor (or friend or family member thereof) to a nicely profitable position. This isn’t hypothetical slippery-slope stuff here — this is how the system was before Civil Service came in.

I know that if I were a hiring manager within the state government, I’d probably find a lot of the Civil Service rules annoying and less than optimally efficient. But more important, if I were an incoming Governor of a certain mind-set, I might find it really annoying that I couldn’t pack more offices with cronies and contributors, and pay off campaign debts by handing out more positions to my partisan allies.

To my mind, that latter is a greater demonstrable risk to the fairness, effectiveness, and representation of government.

I recommend voting NO on Amendment S.

Sorry, don’t get the +5 points for Vets (I assume by this it means ex soldiers).

“A reward for service”. Why? I understand the idea that soldiers have volunteered to defend the country, but why do they need help getting a job? I sort of get the +10 for disabled soldiers, because disabled people suffer discrimination, but should this not be extended to, say, police wounded in line of duty. Why not those with a genetic condition that means the private sector shun them? What about a vital job where 1 in 1000 will die due to their job?

http://www.mypersonalfinancejourney.com/2011/03/cavalcade-of-risk-127-riskiest-jobs.html

I can’t help but think some of the US’s current problems are down to the fetishisation of the military. “Increase the Budget! Throw money at Defence contractors!”

(Hmm, this looks a little more dismissive of you than I mean, but I can’t quite see how to edit it – sorry!)

No, @LH, you have good points there. I would say that as a reward for service (and removing themselves from the job market for a time, even if there is certainly job experience that comes in the service), there’s certainly a nice-to component to providing an extra 5% for the score to military veterans. And, yes, you could extend that to other categories, but vets are something of a sacred cow in American politics as you note — originally because so many Americans actually served, but of late at least in part as a patriotic fetishism exploited by certainly political groups.

Thanks for clear and concise analysis. This really scares me. If it wins I’ll lose faith in the majority of the electorate to make intelligent decisions.

My faith won’t be quite as damaged as yours, Michael, if only because “civil service policy” is about as dry a topic as one can imagine the voters actually facing. I have no idea how it’s doing in the polls. I’m afraid people will look at it, decide it’s some sort of anti-union measure, and vote for it on that basis.