Every four years the US gets into a big internal debate (at least in some circles) about the Electoral College and how it distorts the system from a pure, fine democracy into safe states, swing states, and the potential for winning the popular vote but not the electoral vote.

For my non-US readers (or those here who never quite figured it out in civics class), the race for president is tallied up within each state. Each state has a number of Electoral Votes, based roughly on population, equal to the state’s count of House representatives (population based from the previous census) plus the state’s count of Senators (2 from each state). The District of Columbia gets 3 EVs, though they have no voting members in Congress.

The original plan was that each state would determine how to choose its Electors (everything from popular election to selection by the state legislature), then those Electors would brave the transportation system of the late 18th Century, meet together (as an Electoral College), and elect the president. It’s since gotten a lot more systematic than that, though technically the Electors do get together to cast their vote; all states require their Electors to vote there as directed, so it’s pretty much a formality at that point.

In the majority of states, the Electoral Vote is winner-take-all; if you get the majority of popular votes in a state, you end up with all of that state’s EVs. A few states allocate them more proportionately; Maine and Nebraska allocate one for the winner inside each Congressional District, and their two state-wide Senator votes based on the state-wide winner.

The main critique of the system is that the Electoral College is not proportional to the voting public. It is possible (and has happened) that someone could win the popular vote and lose the Electoral Vote (e.g., barely losing in many states, winning big in a few others). Comparing the EV percentage vs the popular vote percentage in any given election shows this distortion. For example:

- In 1968 (the last time there was serious Congressional discussion of changing this system), Nixon got 301 Electoral Votes vs Humphrey’s 191 and Wallace’s 46 — a 56/36/9% split, even though the actual popular vote was 43/43/14%.

- In the contested 2000 election, Bush beat Gore 51/49% in the electoral vote, but lost 47.9/48.4% in the popular vote.

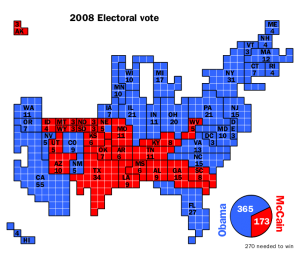

- In 2008, the electoral split between Obama and McCain was 68/32%, while the popular vote was actually 53/46%.

(Some consider this “problem” an advantage, since it tends to exaggerate the victory in the Electoral College, providing more of a national governing mandate; I’m not sure I buy that.)

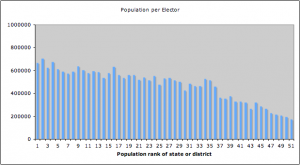

Further, because smaller states still get their 2 Senator votes included, they end up with a disproportionately higher impact per voter (see chart).

(Some folks consider this latter “problem” an advantage, too, and not just those in smaller states. It encourages, in theory, attention be paid to each state, and requires that smaller states have their concerns given some acknowledgment, since the President is not supposed to be the representative of just the majority, but of the entire nation.)

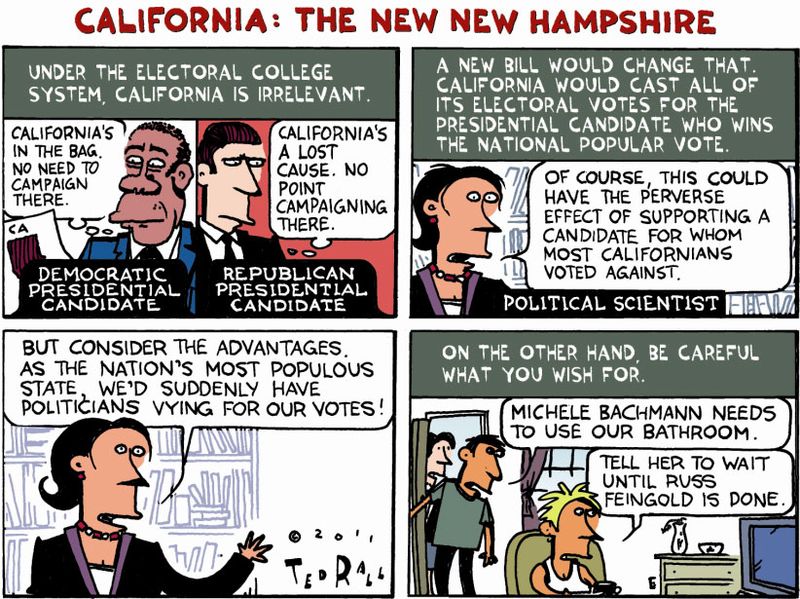

The other critique — particularly apparent this year — is that the contest narrows down into “safe states” and “swing states” purely based on EVs, not on population. A state (say, California) where candidate X has 60% or more of the vote locked up will basically be ignored by both camps because the state’s EVs will all go to the winning candidate. This effectively disenfranchises other 40% of the populate, and can hurt candidates and propositions in other political contests in that state. Meanwhile, “swing states” like Colorado (cough) and Florida and Ohio, where the vote is very close, get “blessed” by many, many, many visits from the presidential candidates, the vice-presidential candidates, their spouses, their proxies, etc., because swaying just a few voters could net all the state’s EVs.

People who suggest amending the US Constitution to do away with the electoral college, though, ignore a couple of resulting problems as well.

First off, it all then comes down to cities and major urban areas. Not much point for a candidate to campaign in New Hampshire, Montana, or even Colorado, if they can get in front of many, many more people by hitting the East Coast megalaopolis, and maybe the LA area. If you can maybe pick up 10,000 voters going to LA, or 100 voters going to Laramie, which are you going to do?

(Sorry, North Dakota — you’re pretty much screwed under either system.)

Second thought is that concerns over voter /election fraud and recounts suddenly become much, much more widespread. In the current system, if Ohio goes to Romney 60-40 (let’s say), then a recount there that might uncover election irregularities is pretty pointless, since it won’t make the 10%+ shift needed. Recounts will focus on the states where the margins are razor thin.

In a purely popular vote, however, in a narrow race nationwide, aggregate cheating and mismanagement has a much greater effect. Fixing 10 votes from every precinct could turn the election. Every state could become another Florida 2000 — because, to be honest, our electoral practices (even where scrupulously honest) are not nearly as rock-solid procedurally and execution-wise as they should be. In an electoral college system, that “noise” gets washed out by the winner takes all practice. When it becomes a national popular vote, though, the impact of hanging chads and voter suppression, etc., become much more significant, much harder to narrow down or audit.

A more practical barrier to changing to an all-popular vote is that it would require a federal constitutional amendment — and previous attempts have demonstrated that smaller and more rural states will oppose that, as reducing their overall influence.

Rep. Steve Israel (D-NY) has proposed an interesting tweak to the system, which would add a bonus 29 electoral votes (equivalent to the state of Florida) to anyone who won the popular vote (sort of a national version of the “proportional electoral vote with a bonus for the winner” schemes in Maine and Nebraska). Not quite sure about the precise number, but it would add an interesting spin to things to prevent a popular/electoral winner conflict. That might encourage a bit more campaigning outside of the swing states (every extra vote counts, at least a little) while not completely overturning the advantages of the electoral system.

Or it might just be adding one more complexity to a distorting process.

It’s not likely to pass (everyone complains about the Electoral College, but nobody in Congress really has a huge desire to fix it, certainly not via a minority party bill), but it’s another example of people trying to fix a system seen as problematic, but with no easy answers that don’t add their own problems.