Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) Rules notes. See the end of the post for notes on 5.5e (2024) rules.

Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) Rules notes. See the end of the post for notes on 5.5e (2024) rules.

Since it comes up periodically and I Here are my notes on how Surprise works in D&D 5e — at our table, at least, given the complexities of Active vs. Passive skills and variations under different DMs.

When Does Surprise Happen?

Surprise occurs when two parties (1+) meet and one of them is unaware of the other until action has begun.

Two thoughts on this:

- A situation where there is obvious risk can’t engender surprise unless an attack comes from a completely unexpected direction. If are aware of danger, and are taking normal precautions for it, you cannot easily be surprised (you can be ambushed, but you won’t suffer the consequences of surprise).

- Trying to be and stay aware has limitations. Even if you know you are in a combat zone, you can only spend so much time and energy watching for bad guys above, below, and in all directions.

Note that “action” usually means “combat,” given D&D’s proclivities, but it doesn’t have to.

The basics are encapsulated thus (broken into points for clarity):

So what happens when the parties meet?

The PHB says (broken into points):

The DM determines who might be surprised.

(Though he’ll try to be fair about it and as impartial as possible.)

If neither side is trying to be stealthy, they automatically notice each other.

E.g., “You round the corner and there is a party of dwarves walking toward you. Both sides stare at each other for a moment … but after that joint moment of, yes, startlement, each party remains on an even footing with each other.”

Or it’s even, both sides are approaching the corner, chatting with each other, hobnailed boots clattering, and they become aware of something around the corner at about the same time. In either case, surprise is moot.

Otherwise, the DM compares the Dexterity (Stealth) checks of anyone hiding [or otherwise trying to be stealthy] with the Passive Wisdom (Perception) score of each creature on the opposing side.

The caveat I added is important; the rules (and a lot of discussion) has to do with one party laying in wait for the other, but it could as easily be trying to creep up on another group. There’s also sort of an arbitrariness here — it’s easy to think of a situation where both sides are trying to be stealthy while listening for trouble … the thief sneaking up on a corner while a guard is waiting for someone to step around the corner, but is unaware of when it will happen. Who gets to make the Stealth check vs the Perception check? Hmmmmm …

Also, note that comment on Passive Perception. We’ll get back to that.

Any character or monster that doesn’t notice a threat is surprised at the start of the encounter. […] A member of a group can be surprised even if the other members aren’t.

There’s a bit of artifice here. While there is a remarkable amount of argument about “a threat,” essentially it means that if you hear any of the orcs who are laying in wait ahead, sufficient to put you on your guard, you will not be surprised by any of them — even, arguably, by the orcish assassin coming up from behind (because there’s no facing, so your presumed awareness is 360° once you’re on the alert).

This last is is important, and is further clarified in the Sage Advice Compendium :

You can be surprised even if your companions aren’t, and you aren’t surprised if even one of your foes fails to catch you unawares.

Surprise, then, is an individual thing for characters (and, to a more limited degree, for opponents): I, as a character, have to detect any of the other side to not be surprised (if I hear one person’s chain mail jingling, I become alert and won’t be surprised). But my not being surprised doesn’t affect my fellow players.

That can seem kind of weird, depending on the timing. But if we’re walking into a trap, my detecting someone is deemed a last-second thing; I can’t shout out, “Hey, it’s goblins! Don’t be surprised!” (Though circumstances can allow that — I’m trying to spot something on the trail ahead, and there’s a glint of metal three switchbacks up the hill … I am allowed to warn my friends in that case.

How Does Surprise Get Determined?

This starts getting into that whole Active and Passive Skill thing.

- Active Skills are when you roll 1d20 and add your Ability and Skill Proficiency scores. They represent an active effort on your part (“I’m trying to do X”).

- Passive Skills are just “what you do most of the time,” and they are served by basically replacing that d20 roll with a 10 (i.e., making it a perpetual average role).

Some DMs out there argue that it also represents the minimum you can get on an Active Skill roll, but I disagree; actively looking for things can allow someone to get distracted (while I’m focusing on telling whether that glint ahead on the trail is steel or a shiny rock, I miss the tripwire across the path I might otherwise have seen).

(See more on Passive Perception here.)

The problem with Passive Skills is that they are meant to represent two things: (1) the “average” background ability and (2) a way for the DM to save time. Rather than have everyone roll Perception (or the roll it themself behind the screen), it’s far easier (and less alerting to the players) for the DM to know that Bob’s Passive Perception is 12, so they will always see a hidden thing with DC10, and always miss one with DC15, unless they are actively searching.

Easier, but kind of dull. “Oh, this floor of the dungeon appears to be populated by DC10 traps. Bob strolls through it with no chance of being caught by any of them.”

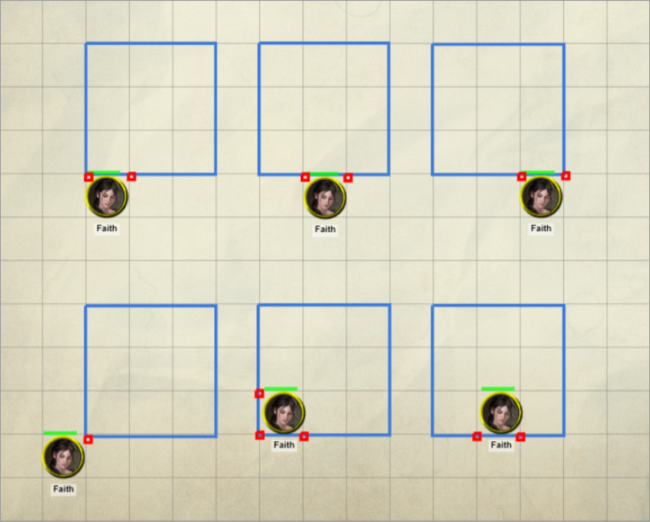

And the “easy” aspect is dubious in Roll20 (or any VTT): I can click on a pre-set macro and roll everyone’s Active Perception any time I want. Not only is it hidden from the players, but it allows for variation — someone other than the highly perceptive Rogue can spot the trap once in a while (though, on average, it’ll still be the highly perceptive Rogue), and it means that if the highest Passive Perception is 15, DC20 traps aren’t automatic hits.

As a general rule, and for DM convenience, the “who rolls this, the Players or the Monsters” is usually focused on the Players (which is more fun for them, but also a lot easier for the DM). So a way to do this is that the Orcs, as they lay in wait, all use their Passive Stealth (effectively the DC number), while the Players all roll their Active Perception (or the DM rolls it for them) — or, if the ambush is on the other foot, the Orcs all use their Passive Perception and the Players all roll their Active Stealth. While the bad guys relying on Passives is kind if dull, it’s much simpler.

Two examples:

Characters Surprising Monsters

E.g., “Hey, here come some monsters, lets ambush them!” (Or perhaps, “There’s a monster camp up ahead, let’s creep up on them.”)

In its most basic form, the players prepare their ambush, and each rolls a Stealth check. It gets compared to the Passive Perception of the target monsters. The problem here is that the big fighter wearing plate mail is always going to have a crap Stealth roll, meaning the monsters (who all have the same Passive Perception) will always hear them.

An alternative, especially if the party has a chance to collaborate and plan and are aware of what the bad guys are doing, is to roll a Group Check (PHB 175, and more written here):

When a number of individuals are trying to accomplish something as a group, the DM might ask for a group ability check. In such a situation, the characters who are skilled at a particular task help cover those who aren’t.

To make a Group Ability Check, everyone in the group makes an Active Ability Check. If at least half the group succeeds, the whole group succeeds. Otherwise, the group fails. That lets the stealthy Rogue counter the noisy Fighter (“Pssst — watch out for that twig you’re about to step on!”). The success usually has to be against a unitary number/difficulty, though, e.g., the Passive Perception of the opposition.

Group Checks can be used for anything, but they’re really designed for when a single individual failure would mean the whole group fails.

Monsters Surprising Characters

This sounds like it should be the same thing, and, ideally, it is, but pragmatically, it’s usually handled a little differently.

So, for example, rather than the DM rolling (Active) Stealth for each of the monsters (fine for one or two, a real problem with twenty), the suggestion is to use the Passive Stealth (10 + DEX bonus + Stealth bonus).

The only problem with using the Passive Stealth there is that a Player who misses (either Passive Perception or an Active Perception roll) misses against all of them, and someone who makes the needed number succeeds against all of them. Unfortunately, that’s the kind of abstraction that is inevitable in this kind of simulation.

Using Active Perception rolls for the Players is probably better (and, if the DM has a macro set up for it, easy).

What Happens When Someone Is Surprised?

Pre-5e there was the concept of a “surprise round” — a round in which the surprisers get to act, and the surprised don’t.

5e changed this a bit. When the first action of an encounter takes place, Initiative gets rolled by everyone (even folk who are surprised). If you are deemed surprised, it means you:

- cannot Move or take an Action (including a Bonus Action) on your first turn

- cannot React until after your first turn

So the band of goblins gets the drop on all your party. Everyone’s initiative rolled and likely intertwined, but as each party member’s turn comes up in the first round, they cannot do anything during during that turn. But once each their turns has come up (and been squandered as they recover from surprise) they can React (e.g., take an Opportunity Attack, cast Shield, etc.).

E.g. Susan and Bob surprise Goblins 1 and 2. They all roll Initiative, and it goes in the order Susan, Goblin 1, Bob, Goblin 2.

- Susan runs past Goblin 1 (who cannot React with an Opportunity Attack because they are surprised) and stabs Goblin 2.

- Goblin 1’s turn comes up; they cannot take any Move or Action and just stand there, agog with surprise.

- Bob decides to finish off Goblin 2. He runs past Goblin 1 … but since Goblin 1’s turn this first round has passed, Goblin 1 Reacts, taking an Opportunity Attack to stab Bob.

- Goblin 2’s first turn comes up; they, too, cannot take any Move or Action … but once their turn is over, if Susan tries to run back to help Bob, Goblin 2 can try an Opportunity Attack, too. And when Goblins 1 and 2 come up in the next round, they will be Moving and Acting as normal.

Would you like to know more?

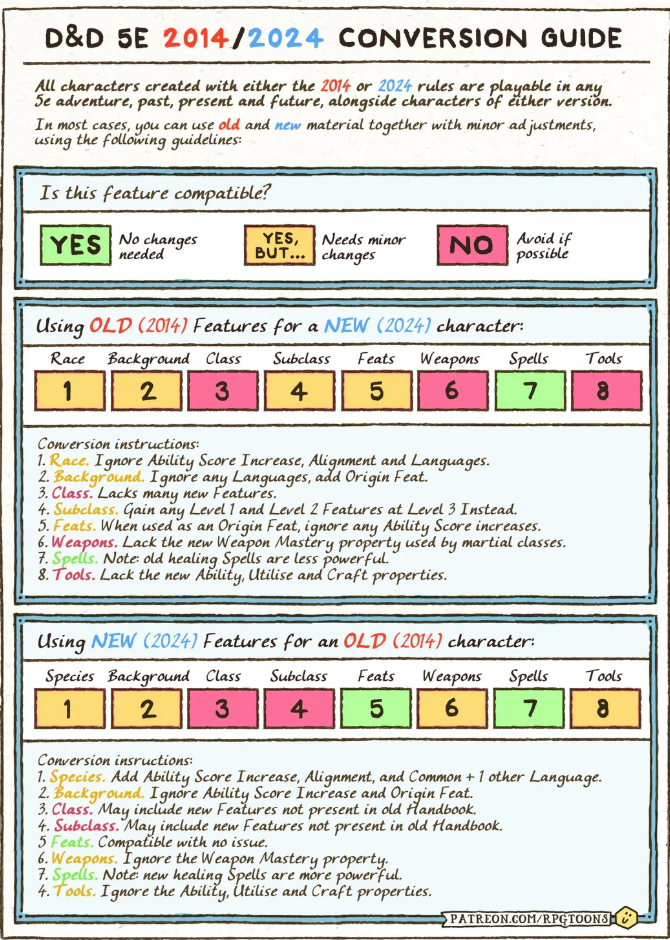

Surprise in 5.5e (2024)

We’ll evaluate at a later time all of the Active/Passive stuff above (the stuff that determines if there is surprise). The meat here is how the effects of surprise

We’ll evaluate at a later time all of the Active/Passive stuff above (the stuff that determines if there is surprise). The meat here is how the effects of surprise

Surprise in 5.5e has been significantly simplified — maybe a bit too much.

Surprised creatures roll Initiative at Disadvantage.

That’s it. No special Surprise Round. No differentiating between types of actions. Roll Init at Disadvantage. Quick characters will (likely) still be pretty high in the Initiative order (but maybe not).

Though it’s worth noting that if the attackers in ambush are successfully (through Hide (with Stealth) or Invisibility) hidden, they get Advantage on the Init roll. Which widens the gap in Init still more.

The upshot of this, though, is that Surprise matters a bit less. Everyone will get to do something Round 1; you won’t have surprisers who effectively get two attacks in, which, in an Action Economy, can be deadly. This is a Good Thing if it’s your party being surprised; it’s a Bad Thing if you’re doing the surprising.

Arguably, this almost takes too much of the sting out of Surprise. The surprisers will still get the first blows in, but the surprised will spring back quickly.

It will be interesting to see how folk end up in their evaluation of it.

Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) and 5.5e (2024) Rules notes.

Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) and 5.5e (2024) Rules notes.

From

From