Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) Rules notes. See the end of the post for notes on 5.5e (2024) rules.

Part of an ongoing series of 5e (2014) Rules notes. See the end of the post for notes on 5.5e (2024) rules.

So in addition to being a Tactical Guy, I’m a role-player, so I will likely emphasize those aspects in any game I can.

D&D is not a RP-heavy system by design; it’s originally derived from miniatures warfare gaming (which doesn’t reward someone running into the middle of the battlefield with a white flag to negotiate a truce), and the Experience Points that folk are incented after are for, frankly, killing things. This has “gotten better” over the years, but killing does still seem to be the best way to get XP. So, as a general rule, one does not hop into a D&D game expecting penetrating psycho-drama and lengthy inter-character dialogs.

Right. Got it.

There Will Be Role-Playing

I still encourage players to think about the personality aspects of their characters — 5e has rather clumsily loaded traits, ideals, bonds, and flaws into the character creation process, related to background. It’s a start, but I would hope players would come up with something a bit more organic, using those background-driven items as, well “inspiration.”

Role-playing is also important, in my games, when encountering people not in the party. The folk encountered, especially in town, are not pop-up clue dispensers. I can’t promise Shakespeare, but there will be character interactions, so I expect something more than “I walk up to the Bartender and roll on Deceive.”

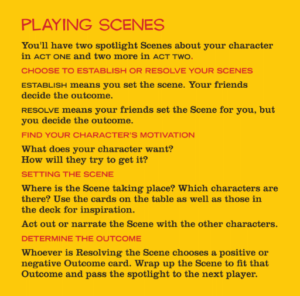

All of which ties into the post topic: Inspiration [PHB 125]!

What is Inspiration?

From a meta standpoint, Inspiration is an optional rule, based on whether the DM wants to use it. I’m not sure why they would not, but if your tables doesn’t use it … it’s worth asking why not.

Mechanically, here’s what the book say (emphasis mine):

Inspiration is a rule the game master can use to reward you for playing your character in a way that’s true to his or her personality traits, ideal, bond, and flaw.

By using inspiration, you can draw on your personality trait of compassion for the downtrodden to give you an edge in negotiating with the Beggar Prince. Or inspiration can let you call on your bond to the defense of your home village to push past the effect of a spell that has been laid on you.

Those examples given are a little misleading. You get Inspiration by (as a limited example) drawing on those personality traits in some fashion … and can then use Inspiration to do something better than usual. RP-wise, you can draw on that connection (“As I talk to the Beggar Prince, I remember that morning giving my last gold piece to that hungry child [for which I got Inspiration because it ties into my character origin], and I hold onto that insight as to what hunger really means as I negotiate for my friends’ release”), but it’s not completely necessary.

Gaining Inspiration

The 5e DMG (pg. 240) specifically suggests giving Inspiration for:

- Roleplaying: A character does something notable and memorable that is consistent with their personality bonds, flaws, nature, etc.

- Heroism: A character does something notably heroic — usually taking some sort of huge risk (with possible loss of life).

- A Reward for Victory: Giving Inspiration when a character levels up is common at many tables. Other noteworthy goal achievements (slaying the BBEG, or even one of their powerful lieuts) can also qualify.

- Genre Emulation: A character helps support the conventions and tropes of the genre — e.g., calling out that they are falling for a dame in a noirish setting because that’s what loner heroes do; leaning into the creepiness and fright of a horror -focused game.

That all seems pretty in line with my thoughts. The PHB similarly says:

Your GM can choose to give you inspiration for a variety of reasons. Typically, GMs award it when you play out your personality traits, give in to the drawbacks presented by a flaw or bond, and otherwise portray your character in a compelling way. Your GM will tell you how you can earn inspiration in the game.

As noted, good role-play will (or should — see below) almost always net Inspiration at my table. Sometimes it might not happen until after the session when I’m doing the game logs, but …

I also give Inspiration for particularly fun, imaginative, or memorable action by a character. If it’s the sort of thing you’d tell stories about afterwards in a tavern, or that might even be mentioned in the Saga of You that some bard will write someday — it’s worth Inspiration. If it’s something that made every player at the table cheer, laugh, or yelp with surprise (and will be told about at gaming tables to come) — it’s probably worth Inspiration as well.

Since the DM controls the reward of Inspiration, you can keep it from becoming too mechanical or from players “gaming” the system for it. Inspiration should feel like a real reward for doing something for doing something that makes the game more interesting, entertaining, or enjoyable for everyone at the table.

One last thing: the DMG also suggests the DM can dangle Inspiration out for someone when they are considering an action that might provide such a reward (e.g., playing Horatius at the bridge to let their friends escape). That makes it feel a bit too transactional and mechanical to me, the sort of thing that deflates the value of Inspiration.

Using Inspiration

If you have inspiration, you can expend it when you make an attack roll, saving throw, or ability check. Spending your inspiration gives you Advantage on that roll.

Basically, any time you roll a D20, you can burn your Inspiration to gain Advantage. It’s not always a game-changer, but it’s a nifty little boost.

Some tables include house rules letting you burn Inspiration to give someone else Advantage, or even to given an enemy Disadvantage. Thematically that’s a bit more dubious; it’s also potentially imbalancing.

Something tangential to the that, though, is this:

Additionally, if you have inspiration, you can reward another player for good roleplaying, clever thinking, or simply doing something exciting in the game. When another player character does something that really contributes to the story in a fun and interesting way, you can give up your inspiration to give that character inspiration.

Don’t let this erode down to players just giving their own Inspiration at the very last second to someone else who badly needs to make a roll. It should most likely happen out of combat, and the giver should provide some justification. (Note, though, that some tables effectively pool their Inspiration together; to me, that robs it of some of its color.)

Use It Or Lose It

Inspiration is a binary — you either have it or you don’t. You can’t earn multiple “points” of Inspiration.

That means that if you do something Inspiration-worthy, and you still have your previous Inspiration, you don’t get anything.

The biggest problem I see with players (myself included, when in that role) is holding onto their Inspiration “just in case.” Better to use it at the first point where it would be useful, and work at earning more. Fireball coming down your throat and you used DEX as your dump stat? Time to spend that Inspiration die to get Advantage on that DEX Save …

The DMG [p. 240] suggests each character should get around one Inspiration a session. That seems a bit high to me (and I’m not wild about an Inspiration quota), but if you have players that are doing solid RP and coming up with interesting ideas, it’s certainly not an impossible rate for them.

Some GMs put some bounds as to how long Inspiration can hang around out there — resetting it at the time of a Rest of some sort, for example. I understand that thematically, and it certainly encourages people to use their Inspiration while they have it, but I tend to be more lenient than that.

Helping the DM

There are a couple of other ways (at my table) that helping the DM can also generate Inspiration.

A player who makes substantive contributions to the game outside of it (keeping game logs, posting lots of funnies in the campaign forum, etc.) might sometimes get Inspiration for their character. I don’t do this every time because I don’t want it to be quite so quid pro quo, but occasional Inspiration is a nice tip-o-the-hat to a helpful player.

I know as a GM that I often have a dozen balls in the air, and keeping an eye out for someone making the game “more exciting, amusing, or memorable” sometimes fails because I’m too busy trying to decide what spell the evil wizard is about to cast.

Because of that, I encourage players to let me know if someone deserves Inspiration. I rarely say no (largely because I’m rarely asked for an unworthy cause).

Closing Thoughts

The DMG [p. 240] has further suggestions of when and why to award Inspiration, and some variants on the rule. It’s worth a read.

I find that players often forget they have Inspiration available when playing in a VTT like Roll20. A simple way around that is to create or designate a token Status Marker for Inspiration. Alternately, I use the Dealer API/Script by Keith Curtis (see here and here) with some simple macros to put (or take) a shiny gold D20 on the player IDs on the Roll20 desktop, complete with an inspiring message. Fun, and very visible so that it doesn’t get forgotten!

How does this change in 5.5e?

First off, it’s called Heroic Inspiration now, probably to help distinguish from, say, Bardic Inspiration (a bardic class feature the lets the bard give another creature a D6 (rises with level) to use on any failed D20 Test in the next 24 hours).

Secondly, it’s no longer an Optional Rule, but baked into the system.

In addition to tweaking the name, the whole thing has evolved from top to bottom.

Using Heroic Inspiration

In the Vocabulary section of the 5.5e (2024) rules, it reads under “Heroic Inspiration“:

If you (a player character) have Heroic Inspiration, you can expend it to reroll any die immediately after rolling it, and you must use the new roll.

So two differences here:

- It’s providing a die reroll, rather than Advantage. Effectively that’s the same, but process-wise it means considering using it only after a failure, rather than “I’ll use my Inspiration, oh, look, I succeeded on both rolls, so that was a waste.” It also helps it stand out against all the other mechanisms that award Advantage.

- The reroll can be on any die roll, not just a D20 Test. Going up against that giant with your great axe and rolled a 1 on that D12 damage die? Now’s the time to try and improve on it! Leveling up and rolling your new Hit Die and score a 2 rather than a 10? Give it another go! Trying to heal your buddy and rolled something crappy in healing HP? Heroic Inspiration to the rescue! Your Wild Magic just did something disastrous? Let’s try our luck again! Death Saving Throw got a Nat 1? No problem!

If you gain Heroic Inspiration but already have it, it’s lost unless you give it to a player character who lacks it.

So you are still limited to a single “on/off” of having Heroic Inspiration, but if you get another one, you can (through some metaphysical concept) pass it on to another player. That seems a little odd (and like a homebrew rule that got formal approval in 5.5e), but there you go.

Getting Heroic Inspiration

But … how do you get Heroic Inspiration in 5.5e? Well, it’s still allowed / encouraged for the DM to award it for good role-playing, as in 5e [DMG 46]

You can also use Heroic Inspiration to reward roleplaying, immersion in the game, and heroism. Use it to incentivize the kind of behavior you want to see in your game, such as acting in character, taking risks, thinking strategically, cooperating well, or embracing the tropes of a particular genre.

The DMG commentary about it has gone from about a full page down to a short sidebar, but it still hits the fundamentals.

There’s also a PHB (p. 13) description:

Typically, DMs reward it when you do something particularly heroic, in character, or entertaining. It’s a reward for making the game more fun for everyone playing.

That last bit is important. It’s not just about the Player, or even the Player impressing the DM, but how the Player’s actions make the game better.

That said, the biggest change here is that Heroic Inspiration is produced through rule mechanics, too, e.g.,

- If you are of the Human species — you get Heroic Inspiration after each Long Rest.

- The Fighter (Champion) subclass 10th level feature “Heroic Warrior” gives you Heroic Inspiration at the start of any turn when you don’t have it (!).

- The Musician (Origin Feat) lets you play a song after any Short or Long Rest and give Heroic Inspiration to some of your allies who hear you.

- Spending a Short Rest in your Bastion will net you Heroic Inspiration.

Those are the mechanics I found; no doubt there are others or, at the very least, others will show up in future source books. Heroic Inspiration is now a more unique tool to tweak new classes, spells, and feats; it will be used. But will it be overused (or, frankly, is it overused now)?

On one hand, giving so many ways to get Heroic Inspiration kind of cheapens it? Charging the orcs to save the orphan you befriended? Epic! Took a nap in your Bastion? Literally ho-hum.

Oh the other hand, people will be more likely to use Heroic Inspiration if they know there are ways they will get it back. Which is no small thing.